… and knowing why that is (and why there’s generally no cumbia in the islands) might tell you a lot about both cumbia and the Caribbean. But sorry, honey, I ain’t the one.

There’s a lot of other stuff of course, from 80s grocery store pop — Tears for Fears may be the world’s most ubiquitous band — to rock en español, salsa, merengue, reggae, and corporate pop. Heard some of that Ke$ha for the first time, and can I say, this is what media conglomerates throw money at these days? To quote the name of a tourist trap Mexican place in the Condado neighborhood of San Juan, “Orale, guey!”

The urban stuff rules of course, which means LOTS of merengue de calle, a bit of dancehall, a (tiny) bit of U.S. commersh hip hop — the latter a music that conquered the globe five years ago only to all but completely recede into U.S.-centered provincialism a few years later. It would seem Lil Wayne doesn’t export well. And oh yes, Pitbull, who, along with mentor Lil Jon, anticipated the way to maximize international saturation would be to go deeper into the club, mining the trendiest house tracks of the year. They certainly speak Americano in this respect.

And, oh yes, reggaeton! You’ll hear the big pop tunes that you get on the radio in the states, autotune ballads. And Don Omar’s self-conscious global cross-pollination never sounded better pumping from a Jeep Wrangler on the north coast of the island.

This is of course the watering down of the wilder cacophonic kuduro that pricked up the ears of a thousand bloggers a few years back, smoothing things out for something more Carnival-ready. Gotta say I miss the dreds, Don.

What doesn’t make it over here, or at least to the Latin radio dominated by Central American tastes in the DC area, is reggaeton’s current throwback phase, exemplified by two of the best songs on PR radio. The first recalls the teched-out DJ Blass stuff that knocked me head-over-heels back in ’04, but with some of-the-moment (at least in Latin pop) autotunage. In PR, they don’t stop at the club, they tear the beach up too. And you’re in the right place if you can’t tell the difference between the two.

Quick digression: one of my favorite tracks of 2010 was the similarly Blass-inspired remix of Bomba Estereo’s “Fuego” by the Frikstailers. With this and moombahton, ersatz reggaeton was killing it last year.

Next, a track by reggaeton’s prettiest pretty-boy, Tito el Bambino. His last album was almost totally ballads underscored by gentle dembows, but here he teams up with my favorite spanish “ragga moofin,” Don Chezina, for a deliberate recall of the proto-reggaeton era of DJ Playero. The beat switches up mixtape-stylee, with some vintage Playero-riddims thrown in for good measure.

Perhaps post-crossover-crash, reggaeton’s nostalgically revisiting its roots.

Speaking of Playero, I scored a couple of mixes (37 and 39) at a record store at the seen-better-days mall/market of Rio Piedras, along with an Omega bootleg. You would think this would be the ideal place for CD-R mixtapes, but you’d be wrong. It does have an amazing food court, though. You know your roast pork’s coming from the right place when you’re getting it from a 350-poung guy named Junior who’s being assisted by an older gentleman with a prominent bypass surgery scar.

Speaking of Omega, he’s more prominent than Daddy Yankee these days. His CDs were everywhere. Check out his own Dembow homage. Fuerte!

I finally came across that universal figure of hood modernity, the bootleg guy, hanging at a pool hall on Luquillo Beach, where the cars are hot, the music is loud, and the ballcaps are askew at impossible angles. And the mixtapes are more expensive than what I get in DC. I tried to go for the 3-for-10 deal I get from the go-go dudes at the Florida Market, only to be told by my very stoned vendor that he works for someone else and can’t make deals. Todos somos trabajadores!

The mambo I got there was some of the most creative music I heard on the island. As it emerges from its convention-establishing phase, mambo is mixing with club sounds in a variety of weird ways. Zombie Nation’s soccer anthem “Kernkraft 400” makes an impromptu appearance among Dominican polyrhythms:

Fútbol is really the path towards global crossover, which, just like capital, is where pop music wants to go.

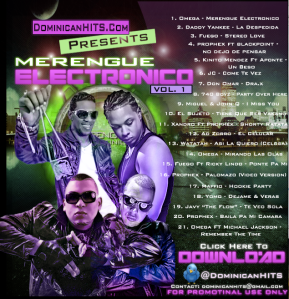

The compilation closes with a timely remix of MJ’s “Remember the Time” (labeled presumptuously “Omega FT Michael Jackson”). I noted the explosion of mambo remixes of Michael Jackson acá.

Here’s the whole compilation, which is the first I’ve ever purchased with a prominent twitter link printed on the cover. Don’t sleep on the merengue remix of 704 Boyz, or the soon-to-blow-up Prophex.

DOMINICANHITS.COM PRESENTS: MERENGUE ELECTRONICO VOL. 1 (103 MB ZIP)

Posted by Gavin Mueller

Posted by Gavin Mueller